“Sometimes it is the people no one imagines anything of who do the things that no one can imagine.”

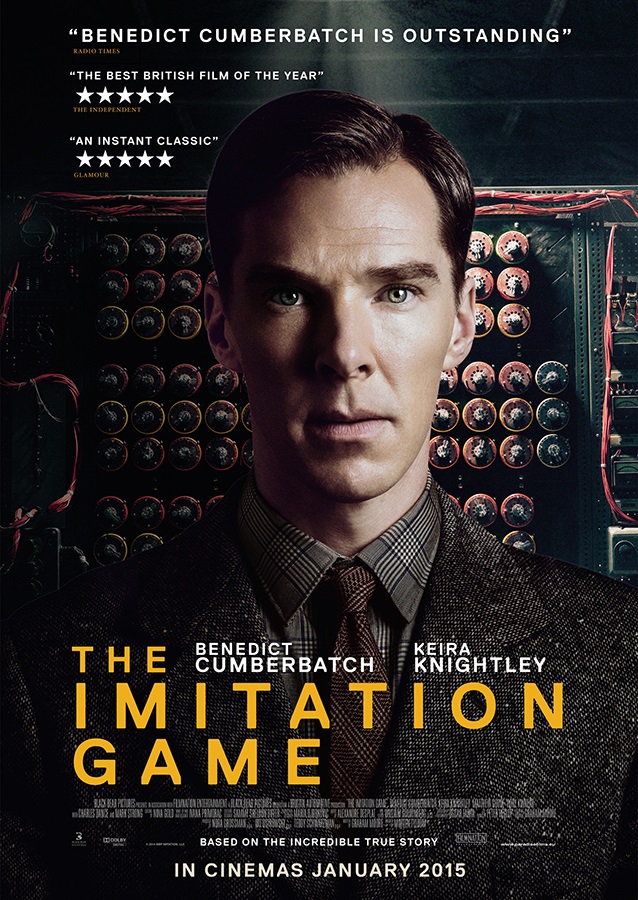

The above phrase is spoken no less than three times in the film, and once in the trailer. It’s an important part of the movie THE IMITATION GAME, directed by Morten Tyldum and starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Keira Knightly. Put more simply, it could be said that sometimes people ignored early in life can end up surprising you.

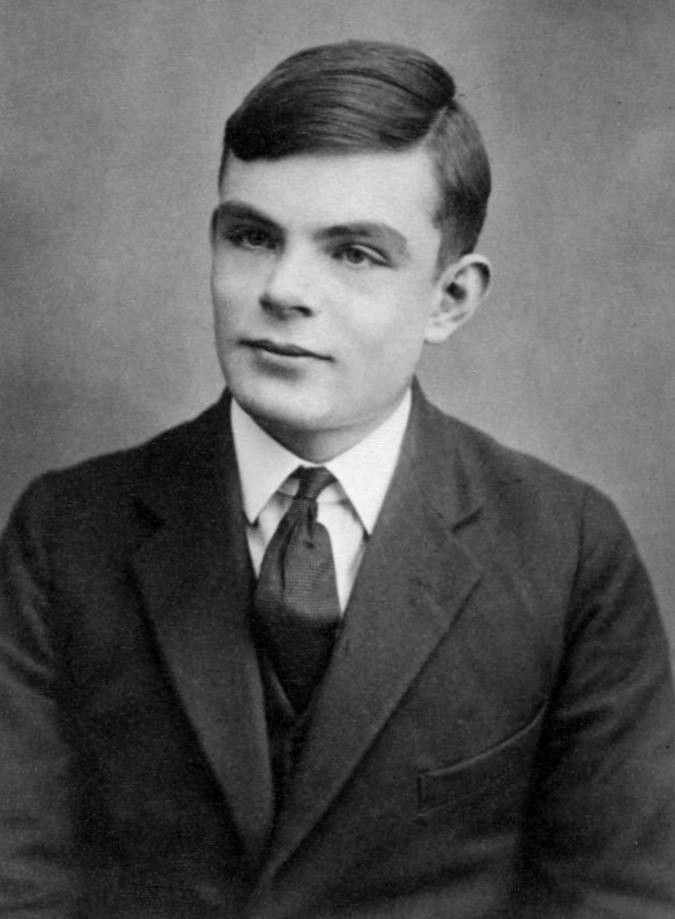

And boy, according to this movie, Alan Turing did exactly that.

And boy, according to this movie, Alan Turing did exactly that.

Turing is credited in THE IMITATION GAME with inventing the computer. In the decades since his death, many works of Science Fiction have made reference to him. I even mentioned him in my own SF novel THE FURNACE. And in a society so dependent on programmable computers and circuit boards and microchips, it makes sense to learn more about this remarkable man — to study the driving force behind his leap from the imagined to reality.

There’s another interesting line in the trailer:

“It took a man with secrets to break the biggest one.”

This one raises eyebrows. Secrets? What kind of secrets?

There was early speculation when the stars of this project were announced that Turing’s sexual orientation was going to be ignored. However, and thankfully so, this couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact, the film touches on Turing’s homosexuality repeatedly: main characters discuss it, Turing admits it, and the final days of his life are even the focus of the film’s conclusion. The outcome was tragic, and THE IMITATION GAME doesn’t shy away from it. Lessons were learned, we’re told. Society is better now. More evolved.

But as I watched the film I couldn’t get over the ramifications of this story. According to the film, one man basically beat Enigma and defeated Hitler. It took extreme perseverance and he had to fight the system in order to build his decoding machine (the first computer?) He was blocked at seemingly every turn, and to finally crack the code he resorted to a series of steps including writing the Prime Minister for help, recruiting more mathematicians for Bletchley Park using a challenging crossword puzzle, and even relying on plain old luck. It’s an incredible tale. Defeat Hitler using a machine no one has ever even conceived of before? End the war quickly and save some two million lives? And to make it even more astonishing, judge the man responsible a criminal for his sexual orientation?

But how much of this movie was true?

Let’s decode the story shown in the movie, and see what’s fact and what’s simply fiction. Afterward we’ll take a brief look at Alan Turing’s place in Science Fiction. Needless to say, BEWARE MASSIVE SPOILERS BELOW. Now, let’s get on with it. In no particular order:

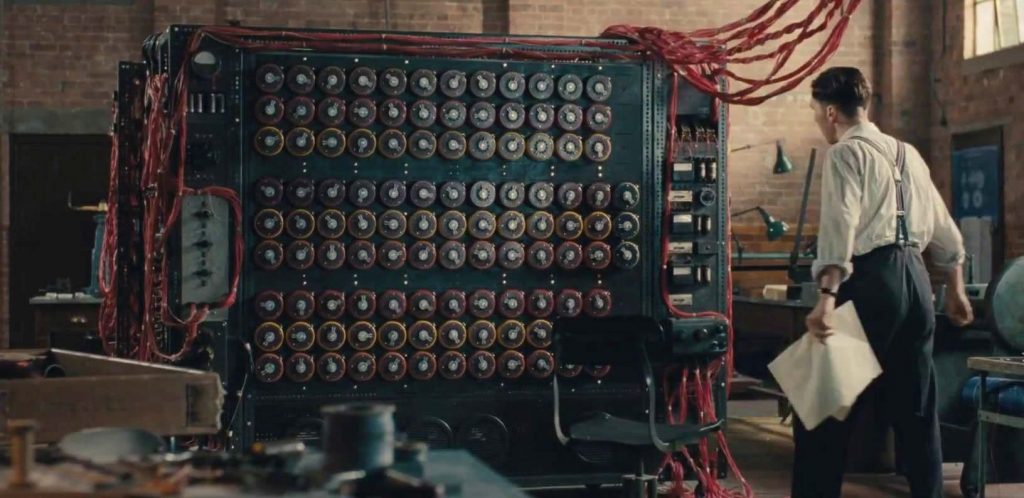

One: Alan Turing takes control of the team and fights Commander Denniston in order to create the “Bombe” machine.

This didn’t happen. It makes for a good story — you always need a strong antagonist, and who better than a commanding officer, especially one from GAME OF THRONES — but Turing was working for Government Code & Cypher School for some time before the war. Denniston was sympathetic to the difficulties involved and was of great assistance to Turing. The film also makes it look as if Turing came up with the idea of the machine on his own. False. In fact, Polish code breakers had created an earlier machine to break Enigma some years earlier. That Enigma code was created by a device that had three gears (not the five that troubled the Allies during the war), and nor did it have a “plugboard”— that row of plugs at the front of the machine that scrambled ten additional letters. The Poles also had help from the French, who supplied them with code-breaking documents stolen from the Nazis. But when Germany upgraded Enigma to five gears, and added the plugboard (both for the Naval variety of Enigma) it simply beat the Polish mathematicians. They had created six “Bomba” machines using Enigma’s own gears (each had twenty-six contacts on it, one for each letter), but when Germany upgraded Enigma just before the war, the Poles realized they’d need to build sixty Bomba machines working in conjunction to do the job.

This didn’t happen. It makes for a good story — you always need a strong antagonist, and who better than a commanding officer, especially one from GAME OF THRONES — but Turing was working for Government Code & Cypher School for some time before the war. Denniston was sympathetic to the difficulties involved and was of great assistance to Turing. The film also makes it look as if Turing came up with the idea of the machine on his own. False. In fact, Polish code breakers had created an earlier machine to break Enigma some years earlier. That Enigma code was created by a device that had three gears (not the five that troubled the Allies during the war), and nor did it have a “plugboard”— that row of plugs at the front of the machine that scrambled ten additional letters. The Poles also had help from the French, who supplied them with code-breaking documents stolen from the Nazis. But when Germany upgraded Enigma to five gears, and added the plugboard (both for the Naval variety of Enigma) it simply beat the Polish mathematicians. They had created six “Bomba” machines using Enigma’s own gears (each had twenty-six contacts on it, one for each letter), but when Germany upgraded Enigma just before the war, the Poles realized they’d need to build sixty Bomba machines working in conjunction to do the job.

The Enigma Machine

They knew they’d hit the wall.

Consequently, they gave all their materials to the British to see if they could figure it out.

Turing was already working at Bletchley, and he threw himself into the problem with enthusiasm. Why? Because Naval Enigma was viewed as uncrackable, so he took a stab at it. You’ve got to admire people with that type of character.

Two: Joan Clarke was hired after finishing a crossword puzzle quickly.

False. Clarke was actually an employee at Bletchley who worked her way from clerk into Turing’s code breaking hut (Hut 8). She did have a mathematics “double first” from Cambridge University (first class honors in two subjects in the same set of examinations) but was denied a full degree because she was a woman. The crossword puzzle makes for a great story … and in fact military intelligence in England did indeed once hire people for Bletchley in that manner. However, the way she was brought into the “team” in the movie is fiction. She was recruited the year before the infamous crossword, and not by Turing.

Three: The machine was built at Bletchley by Turing himself.

False. Turing designed the Bombe machine (it wasn’t “Christopher,” as stated in the movie), but other engineers built it, and not even at Bletchley. In fact, there were thousands of people working there on code breaking — many teams working on various types of codes — while the film makes it seem as though there were only five people.

Four: Christopher was Turing’s friend in boarding school.

This one’s true, and Christopher Morcom did indeed die from Bovine Tuberculosis.

Five: Christopher introduced Turing to ciphers and codes.

In the movie we see Christopher give Turing a book about cryptanalysis. However, this didn’t happen. Christopher was interested in science, particularly astronomy, but it was a later friend who showed Turing his book on code breaking. The movie combined these two people.

Six: Turing asked Joan Clarke to marry him in order to keep her working at Bletchley.

Nope. They were engaged for some time (approximately six months), but this fell apart when he realized his heart lay elsewhere. However, contrary to the film, Clarke did know that he was homosexual — he told her that he had a “homosexual tendency” the day after they were engaged! Back in those days being married was more of a social status that didn’t necessarily correlate with sexual desire. In this sense, the film got it right when Joan pushes to keep the engagement.

Seven: Turing was arrested after a break-in at his apartment led police to investigate his private life.

True. Alan was having a sexual relationship with a man who knew the culprit. Turing provided the description to the police, who wondered how Alan could possibly have known the burglar. Things snowballed quickly and Alan ended up writing a statement which included an admission of his homosexuality — illegal at the time. He ended up pleading guilty to a charge of gross indecency.

Eight: The Bombe machine defeated Enigma and won the war.

First of all, there were hundreds of Bombe machines constructed, not just one. There were some built in the US as well. And there were thousands of people working at Bletchley on cracking codes. There were numerous codes to break: different ones depending on the theater of war (Africa, the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, etc.), particular officers had their own, and there were also ones for different divisions in the military.

First of all, there were hundreds of Bombe machines constructed, not just one. There were some built in the US as well. And there were thousands of people working at Bletchley on cracking codes. There were numerous codes to break: different ones depending on the theater of war (Africa, the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, etc.), particular officers had their own, and there were also ones for different divisions in the military.

This brings up an additional piece of interesting trivia: sometimes the allies didn’t want enigma machines and code papers captured. If this happened, and the German military found out, then the Enigma settings would be changed immediately. However, if the Allies had already broken Enigma, and were actively decoding dispatches on a daily basis, then this would set Bletchley back some. They wanted the Nazis to think the code was still secure. In this way the Nazis were overconfident. Even when convoys were re-routed to avoid U-Boats — and obviously so — the German military couldn’t come to believe that Enigma had been compromised. Instead they thought it was the result of traitors in their U-Boat bases in France.

Nine: Turing committed suicide.

This one’s more difficult to answer. Turing’s mother claimed it was an accident. Apparently Alan was clumsy and mistakenly killed himself with cyanide that he was using for electrolysis to gold plate a kitchen utensil. Her proof? There was no suicide note. There was, however, a note of reminders that he had planned to do the following week. His work papers were in disarray, not in a condition someone suicidal would leave them. He’d also booked some time in a lab at work the following Tuesday evening. There were also theater tickets purchased for some future time, an acceptance to an official function to take place in only seventeen days, and he’d planned to meet a friend the following month. There was a half-eaten apple at his bedside, and rumors persist that he may have used that to “deliver” the poison. (Interestingly, there is also an unproven rumor that Apple chose their logo based on this evidence. At one point Apple employees had said that this was true, but then later the logo designer claimed that the “bite” is there for scale and he was unaware of the Turing connection at the time. Steve Jobs remained silent on the matter.) Turing did, however, create a new will in February of that year, four months before his death. Telling, perhaps, or possibly mere coincidence.

Ten: Alan Turing wrote Winston Churchill asking for permission to lead the team.

Didn’t happen. HOWEVER, he did write the Prime Minister, with the knowledge and participation of other code breakers, asking for more staff in multiple areas at Bletchley. Turing had noticed that the sheer volume of messages to break was bogging them down and they were falling behind. It worked. Upon receipt of the letter, Churchill told his staff to “give them whatever they wanted.” By 1942, Bletchley Park was decoding more than one message every minute, or 50 000 a month.

Eleven: The bonfire at the conclusion of the movie.

This did indeed happen — Bletchley burning secrets after the war — but Turing was not there at the time.

Twelve: The authorities knew the identity of the spy at Bletchley.

John Cairncross wasn’t discovered until the 1950’s. It makes for an interesting bit of drama — Turing a suspect? Could he have been the spy? — but it was simply fiction.

Alan Turing

So what does all this tell us about the movie THE IMITATION GAME? Was it an excellent film? Absolutely. The history of Enigma and how Bletchley and Turing broke it is solid foundation for a highly compelling story. As for the actual events of the period, however, it would be more accurate to say “Inspired by True Events.” Writer Graham Moore did a marvelous job setting up the tale, and the notion of a man fighting the system (on his own) in order to build a machine no one had ever conceived of before to defeat Hitler is compelling. It neglects the work of others who came before him, however, along with thousands of others working to the same end. Turing was a great man and his story is tragic, and in the end, perhaps it’s a good thing that at least we learned that much about him. His legacy lives on in film and screen, and the connection to Science Fiction is clear. There’s an article on Turing’s many appearances in SF over at io9, and I won’t dwell on it, but suffice to say that his impact on technology, the computer age, and genre fiction surely resonates on. (His influence extends from William Gibson to Doctor Who and even to the board game Monopoly.) How could we, as a technological civilization dependent on programmable computers and microchips and circuit boards, not study and memorialize someone considered most responsible for technology as we know it? Alan Turing should be viewed as a visionary who not only challenged the status quo in terms of technology, but also as a man who pushed the UK and the developed world to accept that a “criminal” could in fact be a “national treasure.”

In short, THE IMITATION GAME is a compelling and engaging film, and the notion that the Allies beat Hitler using “modern” technology, in part created by a man whose sexual orientation was criminalized at the time, is a powerful source of drama. TSJ’s Rating: 9/10

Sources

Hodges, Andrew. ALAN TURING: THE ENIGMA. Vintage Books. London. November 30, 2012.

Alan Turing: Inquest’s suicide verdict ‘not supportable’. June 26, 2012.

http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-18561092

Joan Clarke, woman who cracked Enigma cyphers with Alan Turing. November 9, 2014.

http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-29840653

Crossword blog: Saving the world, one clue at a time. August 25, 2011.

http://www.theguardian.com/crosswords/crossword-blog/2011/aug/25/crossword-blog-saving-the-world

International Business Times. The Imitation Game: Who Was The Real Joan Clarke? November 14, 2014.

http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/imitation-game-who-was-real-joan-clarke-1474909

The Greatest Fictional Versions of Alan Turing. io9. November 27, 2013.

http://io9.com/the-greatest-fictional-versions-of-alan-turing-1472836357

Article updated 24 May 2023.

THE SHADOW OF WAR IS OUT NOW!

Watch THE EXCITING BOOK TRAILER HERE!

“The Shadow of War is a slambang thriller set in an all-too-plausible future. Fans of Tom Clancy and Michael Crichton will be spellbound.” — Robert J. Sawyer, Hugo Award-winning author of The Oppenheimer Alternative

“Johnston presents readers with a diverse set of characters, along with a complicated world for them to navigate. The novel shines when describing the technology, as when the characters discuss the beam weapon, nicknamed ‘The Water Pick’ … Fans of high-tech SF will enjoy the concepts and worldbuilding here …” — Kirkus Reviews

“Any good heist consists of three components: a team, a plan and something worth stealing. ‘The Shadow Of War’, the fifth novel in Timothy S. Johnston’s ‘Rise Of Oceania’ series, has all three … Johnston has written a thriller with hot-off-the-presses technology, edge-of-your-seat moments, separated into heart-pounding seconds, and characters who don’t always do what they’re supposed to.” — SFcrowsnest

“Johnston weaves an engrossing tale … it’s easy to highly recommend The Shadow of War as an outstanding and gripping sci-fi technothriller.” — Midwest Book Review

“I need to see Oceania on the big screen!” — FIVE STARS from Readers’ Favorite

“…a terrific read! Smart, thrilling, intriguingly plotted and, like all previous entries in Johnston’s ‘Rise of Oceania’ series, A-level entertainment. And that opening chapter—WOW! Page-turner is an understatement.” — Michael Libling, author of Hollywood North: A Novel in Six Reels and The Serial Killer’s Son Takes A Wife

———

TSJ’s Awards

Follow TSJ on Facebook

Follow TSJ on Twitter

Follow TSJ on Instagram

Enter TSJ’s contests here

Enter your email into the widget at the right to follow TSJ’s blog Life After Gateway.

THE WAR BENEATH: FIRST PLACE 2018 GLOBAL THRILLER Action / Adventure Category Winner, 2019 Silver Falchion Award Finalist, 2018 CLUE Award Semi-Finalist, 2019 Kindle Book Awards Semi-Finalist, & 2019 CYGNUS Award Shortlister

THE SAVAGE DEEPS: FIRST PLACE 2020 CYGNUS Award Winner, 2019 GLOBAL THRILLER Awards Finalist, 2022 Kindle Book Awards Semi-Finalist; 2019 CLUE Award Shortlister

FATAL DEPTH: FIRST PLACE 2021 GLOBAL THRILLER Award Winner, 2022 Silver Falchion Award Finalist (Best Action Adventure), 2021 CYGNUS Award Semi-Finalist

Praise for THE WAR BENEATH

“If you’re looking for a techno-thriller combining Ian Fleming, Tom Clancy and John Le Carré, The War Beneath will satisfy … a ripping good yarn, a genuine page-turner.” — Amazing Stories

“One very riveting, intelligent read!” — Readers’ Favorite

“If you like novels like The Hunt for Red October and Red Storm Rising,

you will certainly enjoy The War Beneath.” — A Thrill A Week

“If you’re here for thrills, the book will deliver.” — The Cambridge Geek

“… an engaging world that is highly believable …” — The Future Fire

“This is a tense, gripping science fiction/thriller of which Tom Clancy might well be proud . . . When I say it is gripping, that is the simple truth.” — Ardath Mayhar

“… a thrill ride from beginning to end …” — SFcrowsnest

“… if you like Clancy and le Carré with a hint of Forsyth thrown in,

you’ll love The War Beneath.” — Colonel Jonathan P. Brazee (RET),

2017 Nebula Award & 2018 Dragon Award Finalist

“Fast-paced, good old-fashioned Cold War espionage … a great escape!” — The Minerva Reader